| For more information about this article or gallery, please call the gallery phone number listed in the last line of the article, "For more info..." |

March Issue 2003

Benny Andrews: The Human Spirit Series at Winthop University Galleries in Rock Hill, SC, Through March 30, 2003

The following comes from a catalogue of the exhibit Benny Andrews: The Human Spirit Series, now on view through March 30 in the Winthrop University Galleries in Rock Hill, SC:

Benny Andrews

The Human Spirit Series

This publication was made possible by Winthrop's Patrons of the Gallery in an effort to further understanding and appreciation of the visual arts at Winthrop University and in the community at large. Additional support for Benny Andrews: The Human Spirit Series was provided by the College of Visual and Performing Arts, the Winthrop University Research Council, Rock Hill School District Three and Rock Hill's No Room for Racism Committee. This project was also funded in part by the South Carolina Arts Commission which receives support from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Winthrop University Galleries and its programs are free and open to the public. The Rutledge and Elizabeth Dunlap Patrick Galleries are located in the historic Rutledge Building, and the Edmund Lewandowski Student Gallery is located in McLaurin Hall on the campus of Winthrop University in Rock Hill, S.C.

Andrew J. Svedlow, Dean

College of Visual and Performing Arts

Jerry Walden, Chair

Department of Art and Design

Tom Stanley, Director

Winthrop University Galleries

Student Gallery Assistants

Kelly Keith

Reed Elliott

John Hill

LaRuchala Murphy

Jon Prichard

Felicia Strickland

Catalogue

Design: Beth Melton

Editing: Jamie Larsen and Karen Martin

Winthrop University Galleries

Rock Hill, SC 29733

803/323-2493

Email: (stanleyt@winthrop.edu)

Website: (www.winthrop.edu/vpa/galleries/events.htm).

Cover: The Carroll School (A Rosenwald School), photo by Queenie Little

© Essay copyright by Richard Gruber

An artist gallery talk and exhibition of Benny Andrews' American Series helped mark the opening of the renovated Winthrop University Galleries in 1991. The painting titled Preacher from Andrews' Revival Series was also featured in Winthrop's 1995 exhibition New South Old South Somewhere In Between. Benny Andrews is no stranger to Winthrop. However, this exhibition of selected works from Andrews' The Human Spirit Series demonstrates a major effort on the part of this university gallery to extend the voice of the artist and his work to the lives of our students and greater community. Benny Andrews is a major figure in American Art whose desire to spread a vision of art and life is matched only by his generosity. Born November 13,1930, in Madison, Georgia, he has not forgotten that his artwork and his success emerged from the Southern roots where he and his family were sharecroppers during a difficult era in our country's social history. Andrews has fashioned these early realities into life-affirming images. His Human Spirit Series is only one more representation of this affirmation.

With Andrews' artistic and social experience as a backdrop, Winthrop University Galleries is pleased that Rock Hill School District Three has embraced this project as one means to initiate their Rosenwald School Social Studies Curriculum to 5th grade classroom teachers. Benny Andrews will be a guest speaker at the district's annual staff development workshop and will provide a hands-on workshop for the art teachers in the district as they formulate an art curriculum for the Rosenwald School project to focus on life in a Depression Era field school. Additionally, Benny Andrews will be the keynote speaker at a City of Rock Hill No Room For Racism Sunday Social. This will be the first time that an artist has addressed this community-based group whose purpose is to foster racial understanding. Finally, Andrews will provide a public gallery talk about his work at Winthrop's Rutledge Gallery. These activities are typical of Benny Andrews' desire to make a substantive difference in the community where his art is exhibited.

Winthrop University Galleries would like to thank Dr. Sarah Lynn Hayes, Queenie Little, Kathe Stanley and Jimmie Matthews of Rock Hill School District Three for their interest and cooperation. We would also like to thank Phyllis Fauntleroy, Delores Brown, Diane Wells and Dr. Ann Cain of the No Room For Racism Committee for making the Benny Andrews Sunday Social possible. Since Winthrop exists within a state university culture rather than a museum culture, the many demands that a project of this caliber has placed upon Winthrop's support offices are unique at best. As such, the galleries would like to thank Winthrop's offices of development, purchasing, university relations, printing services and facilities management for their willingness to help make The Human Spirit Series a reality at Winthrop. I would especially like to thank Jamie Larsen of the College of Visual and Performing Arts for her care and constant concern.

We are most grateful to Winthrop's Patrons of the Gallery who have contributed so generously of themselves to ensure this exhibition and its outreach projects would come to Winthrop and our community audiences. The support of Winthrop's Research Council, the College of Visual and Performing Arts and the South Carolina Arts Commission have been vital. The participation of Andrews' scholar Dr. Richard Gruber has been instrumental in shedding appropriate light on the artist and his work. And finally, we are most grateful to Benny Andrews whose work and presence has enlivened our understanding of how art can indeed affect our lives.

Tom Stanley, Director

Winthrop University Galleries

Having just joined the church, at about age ten, Benny was the first soul I ever heard describe heaven in finite detail. One day while walking through the wilderness (blackberry picking) with Sister, Shirley, and myself, Benny took it upon himself to explain heaven to us young heathens. He explained going to heaven so beautifully, especially the part about all the grapes you could eat, that I wanted to go right that moment. The only thing that cooled me down was his telling me that I had to die first.

-Raymond Andrews, 1990 1

One of Benny Andrews' recent compositions, A Baptist Heaven, which is a centerpiece of this exhibition at Winthrop University Galleries, was inspired, like much of his life's work, by memories of the artist's early years in Georgia. From an early age, as suggested in a passage selected from the memoir published by his younger brother, the noted writer Raymond Andrews, Benny Andrews has not been reluctant to describe his response to the larger issues in life, including his vision of heaven. At the end of the 1990s, as he entered his Connecticut studio to begin a new series of images of heaven and the afterlife, he naturally recalled his own experiences in the rural Plainview Baptist Church and the intense visions and emotions associated with that church's annual revival meetings.

The creation of a significant work like A Baptist Heaven offers insights into the artist's mature methodologies as well, including his willingness to allow a project to evolve from one concept to another, as became apparent when plans for his Heaven Series evolved into the Human Spirit Series featured in this exhibition. In a recent interview, the artist described his concept for this work and its role in a series depicting views of heaven.

With this in mind, the artist decided to begin a series because, as he described it, he felt that he has been "living a very unique existence, living this long and going through all these phases. It would be worthwhile for me to make a contribution to depict that, as historians, artists and chroniclers do." After completing his large-scale collage composition however, he studied it and made a decision. "I thought, well, that's all right. But that's too narrow. My world is bigger than that. So, I went and asked some of my Jewish friends about what they had been told about dying and the afterlife. And they all shrugged, saying they did not remember." After that, he decided not to venture beyond, not to explore issues unrelated to the Judeo-Christian concepts he understood. With that in mind, he selected another direction for the figures to be depicted in his new series.

These comments from the artist offer insights into the evolution of the specific works featured in The Human Spirit Series. However, a larger system of personal experiences contributed to the formation of this recent project. To understand these works, one must know something about the life of Benny Andrews as well as his family's place in the history of the modern South. Accordingly, the remainder of this essay will be divided into two sections, one considering the artist's place in Morgan County, Georgia, in the years from his birth in 1930 until his departure for service in the Air Force in 1950. The second, covering the period from 1950 to 1970, included his departure from the South, his professional training, the establishment of his professional career in New York and the beginnings of his role as a social activist. During these years he began to see his life within a larger historical perspective and came to understand the broader nature of the human spirit, including the determination shown by the pioneers of the Civil Rights movement, as well as in the lives of those who shaped his beginnings in Georgia.

When the New England schoolteachers came South after the Civil War to Morgan and other counties to teach the black freedmen (and women and children), they set up schools in the local churches. When I started school in 1939, classes in Plainview (as in many other Southern black rural areas) were still being taught in a church building, Plainview Lower Church. Like all country grade (elementary) schools of the day, Plainview included grades one through seven, in addition to the pre-primer and primer grades where beginning pupils learned the alphabet and reading and writing. All text and library books were passed down to us, used, from the white schools ....

--Raymond Andrews, 1990 3

An important earlier work featured in this exhibition, The First Day, reflecting the artist's memories of his childhood educational experiences in Morgan County, was completed in 1965, after the artist returned to the South from New York to complete research for the project he called The Autobiographical Series. Traveling under the auspices of a John Hay Whitney Foundation Fellowship, he toured the South in a station wagon with his wife and three children, searching for the remaining traces of the rural, pre-war South he remembered from his childhood. He soon discovered that it was a very different environment than he remembered, marked by an evolving agricultural landscape and the related movement of many rural families to urban and suburban lifestyles.

During the Civil Rights era, as in the Depression, determination and a willingness to strive against seemingly insurmountable odds contributed to the emergence of a new Southern environment, one where social and cultural change took place even in the face of violent and prolonged resistance. Recognizing this, he returned to his New York studio and completed his Autobiographical Series devoted to the passing history of an earlier South, one that had been crucial to his formation. During the summer of 1965, he described his philosophy to a reporter from Atlanta. "My work depends on the South. That's the kind of feeling I have. Whatever I paint is really associated with poor people because those are the people I know."4 While many of the details of farming, small town life, rural education and daily social interaction had changed by the 1960s, the essential spirit that marked those who labored for positive change in the region had not changed. His recognition of that continuum in the human spirit marked both his early and most recent series, linking them in essential ways.

Benny Andrews first left his native South in 1950, when he enlisted in the United States Air Force. During World War II, military service had been one of the most direct paths for African-Americans to leave the South, just as it would be during the years of the Korean War. After four years of training and service as a military policeman during the Korean War era, Benny used his GI Bill benefits, supplemented by proceeds from a little-known fund associated with the University of Georgia's "separate but equal" educational system, to attend art school at the Art Institute of Chicago. 5 After he moved to Chicago in 1954, he discovered the presence of many African-Americans, including members of his own extended family, who had moved from the South seeking a better life for themselves and their children. Even in rural Georgia, he and his family regularly read The Chicago Defender and other African-American papers, keeping them attuned to major national issues. While studying in Chicago, from 1954 to 1958, he watched the South from a different perspective, following the course of the emerging Civil Rights movement and noting the increasing national interest in the region of his birth.

After he moved to New York in 1958, he and his brother Raymond watched together as the Civil Rights movement swept across a resistant South. They watched Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes integrate the University of Georgia in 1961, the school that Benny and Raymond could not attend because of their skin color. They saw photographs of the firebombing of a Freedom Rider bus outside Anniston, Alabama, and followed James Meredith's efforts to integrate the University of Mississippi in 1962. They watched, in 1963, as Medgar Evers was killed in Jackson, Mississippi; as four girls were killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham; as Eugene "Bull" Connor used fire hoses and police dogs to dispel peaceful protestors, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., in Birmingham and as George Wallace announced "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever." And they followed the march on Washington, where Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his historic "I Have a Dream" speech. 6

Returning to New York from the South, the artist completed his Autobiographical Series and exhibited his works at the prestigious Forum Gallery in Manhattan. Then, angered by his dealer's reluctance to exhibit works depicting the ordinary people of his native region, many of them black, he left this gallery and entered a period of social activism, advocating for more equality in museums and galleries. For more than a decade, he was known as one of the nation's leading advocates for bringing the principles of the Civil Rights movement to the art world. In January of 1969, for example, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) was organized in his New York studio. Soon after, he, Raymond and other family members joined protestors who marched at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, calling for an end to discriminatory policies at that museum. From 1970 to 1976, he worked on a body of large-scale works, The Bicentennial Series dedicated to African-American history for the Bicentennial celebrations in 1976 (a series scheduled to serve as the subject of a major exhibition at the Wadsworth Athenaeum in the fall of 2003). 7

Actually, in my case, racism was just one of the many problems I had. I had a class problem, too, you see. My family (was) probably one of the poorest, especially when we were sharecroppers in the county-and I'm just talking about Morgan County now. We were probably as poor as could be .... So there were so many things-it was not just to fight being a black person in a white society: it was also to fight being a poor person in a total society-being both black and white.

--Benny Andrews, 1975 8

When Benny Andrews was completing his Bicentennial Series he spoke to a journalist from Georgia, offering this evaluation of the challenges his family had faced during his childhood in Morgan County. More recently, reconsidering the sentiments he had expressed in this earlier quotation, the artist stated that today he would add another liability to this list-being from the country, instead of being from a town or city. "I was seen as being truly country all the way into my entrance at the Art Institute in 1954." To really understand the artist and his aesthetic philosophy, as expressed in his Human Spirit Series, it is important to consider his relationship to a specific time and place in the South. Looking back, in the beginning of 2003, Benny Andrews recognizes the critical roles played by his parents and a small number of other individuals-both black and white-during his life in Morgan County from 1930 to 1950. In general, these modest people never received the acclaim given to the Civil Rights pioneers or other prominent figures of the era. Instead, in quiet and determined ways, they served as role models for what was morally right, even in the segregated atmosphere of the era. Perhaps surprisingly, as he remembers, it was also a time when Morgan County and the city of Madison supported a vibrant African-American community. For Benny's family, it was a period when American social norms and myths were conveyed to them significantly through the movies, radio and popular culture.

Benny Andrews was born in Plainview

in 1930. His family history and blood lines reflected the complex

history of racial relations in the South. His paternal grandfather,

James Orr, was the son of a prominent white plantation owner,

and his paternal grandmother, who was also the midwife at his

birth, was known as Jessie Rose Lee Wildcat Tennessee. She was

of mixed race, with black and Indian blood, as were his maternal

grandparents, John and Allison Perryman. George Andrews, his father,

spent much of his life laboring in the cotton fields of Morgan

County. Later in life, he became recognized for his self-taught

art works, earning the name of "The Dot Man" as well

as regional and national attention in museum and gallery exhibitions.

9 His mother, Viola Perryman Andrews, a forceful presence

in the life of the family, encouraged all of her children to write

and to draw, often decorating their home with the products of

her children's imaginations. Education was a critical issue for

his mother, evident in her encouragement of Benny's efforts to

graduate from Burney Street High School in Madison, and then to

become the first family member to attend college.

The cotton fields of Plainview defined the annual rhythms and

activities of the Andrews family. School attendance was irregular

for the Andrews children, allowed only around the cycles of cotton

planting and harvesting, reducing Benny's attendance to about

five months a year. Reflecting his early family realities in the

Autobiographical Series he painted a black farmer laboring

behind mules in a cotton field while his wife scrubbed wash in

a tub on the front porch of a wooden house (Southern Landscape,

1965, Collection of the Morris Museum of Art). No doubt, it

was a familiar scene to the artist. In Death of the Crow

(Collection of The Ogden Museum of Southern Art, University of

New Orleans), he depicted a black man in coveralls looking at

the sprawled body of a dead crow, symbolic of the passing of the

"Jim Crow" South and the transition to a new order marked

by the end of the cotton economy that had defined the history

of his family.

Recently, as he reflected upon the works included in this and a series of related exhibitions documenting the evolution of his career, and as he considered questions asked by the author for this essay, Benny Andrews offered new observations and insights into the importance of the figures associated with his early life and his childhood environment. He also responded to inquiries about his ability to survive the challenges of these years, and his ability to retain a positive philosophy in spite of the adversity faced by his family. Looking at the general conditions of the period, he used the weather as a metaphor. "If you think about the weather, we literally lived up against the weather in the community. And the community was a whole, as it had to be." Continuing, he offered insight into the distinctive character and importance of the larger local community.

Then, within this larger geographic and physical context, there were specific influential people who were vital to the health of the community. This sense of community, and of a sense of specific qualities associated with life in Morgan County, remains of particular interest to the artist in his later years.

Benny Andrews learned much from his parents. From his mother he acquired a sense of tenacity, as well as a strong sense of responsibility. She consistently reminded Benny and all of her children that they were no worse, and no better, than anyone else, regardless of skin color, education or social status. For the light-skinned members of the Andrews family, including Benny, this became an increasingly important lesson to remember. From his father he learned about the incessant need to create, with whatever materials were at hand, even if that meant drawing in the red Georgia soil with a nail or a stick.

From his father, as he recently recounted, he absorbed a rich and complex range of lessons, including lasting impressions about the value of a strong work ethic as well as the destructive impact of racial stereotyping and the related definition of an individual's self-worth based solely upon the color of one's hair and skin. He learned, as he explained, to accept himself on his own terms.

By accepting these realities, and by adhering to these principles, whether he was living and working in a rural or highly urban environment, he found that he was able to maintain the strategic course he hoped to set for his life and his career. And, as was evident from a closing comment by the artist, it suggested much about the philosophy behind the series that is the subject of this exhibition, focused on the endurance of the human spirit.

J. Richard Gruber, Director

The Ogden Museum of Southern Art University of New Orleans

January, 2003

1 Raymond Andrews, "The Last Radio Baby" (Atlanta: Peachtree Publishers, Ltd, 1990), 68.

2 Interview with Benny Andrews, January 4, 2003. This, and all following quotations from the artist, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from a continuing series of interviews with the artist conducted over a period of years in locations including New York, Georgia, Connecticut and New Orleans.

3 Raymond Andrews, "The Last Radio Baby", 141.

4 Linda Greene,"Artist Looks To The South," ("The Atlanta Journal/The Atlanta Constitution," Sunday, August 1, 1965), 9-D.

5 Gylbert Coker recently discovered that the actual system established to support this program was initiated in 1943 by the University System of the Georgia Board of Regents. "In 1944 them was $2,398 set aside for twelve Negro students. By 1950, $300,000 had been set aside for 2,700 Negro students" See "The Art of Benny Andrews" (Thomasville, Georgia: The Thomasville Cultural Center, 2002), unpaginated.

6 See Calvin Trillin, "An Education in Georgia" (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1991 ed.) 3; and Juan Williams, "Eyes on the Prize, America's Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965" (New York: Penguin Books, 1988), 205.

7 For more information on this period of his career as well as the broader scope of his earlier life, see J. Richard Gruber, "American Icons: From Madison to Manhattan, the Art of Benny Andrews, 1948-1997" (Augusta: Morris Museum of Art, 1997).

8 Interview [with Benny Andrews], "Ataraxia 4", 1975, 8.

9 See J. Richard Gruber, "The Dot Man: George

Andrews of Madison, Georgia" (Augusta: Morris Museum of Art,

1994).

Benny Andrews was born November

13, 1930, in Madison, Georgia. With a small scholarship he briefly

attended Fort Valley State College in Georgia. In 1950, he joined

the United States Air Force and served during the entire Korean

War. In 1954 he entered the Art Institute of Chicago on the GI

Bill. After graduation in 1958, he went to New York to begin his

life as a professional artist. Andrews' works are in numerous

public collections including The Detroit Institute of Arts, The

Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, The Metropolitan Museum

of Art, The Museum of Modern Art, The High Museum of Art and The

Ogden Museum of Southern Art. He has received critical acclaim

in numerous articles and publications including J. Richard Gruber's

extensive work, American Icons From Madison to Manhattan the

Art of Benny Andrews, 1948 - 1997.

Exhibition Checklist

Oil and Collages on Canvas

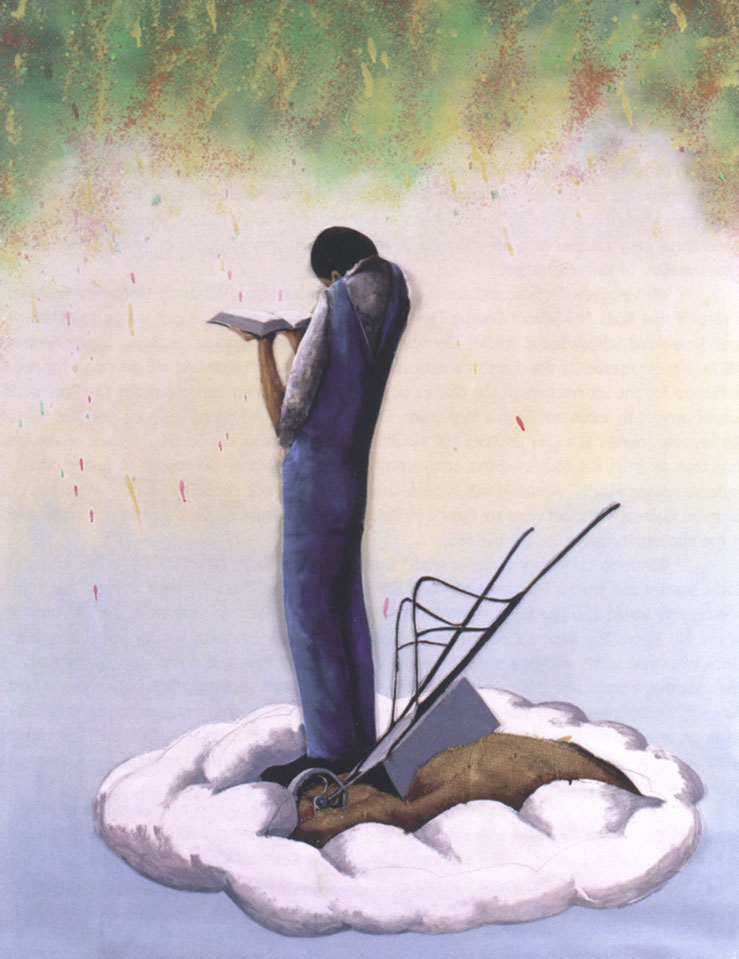

1. Farmer, 2000,107 1/2" x 50"

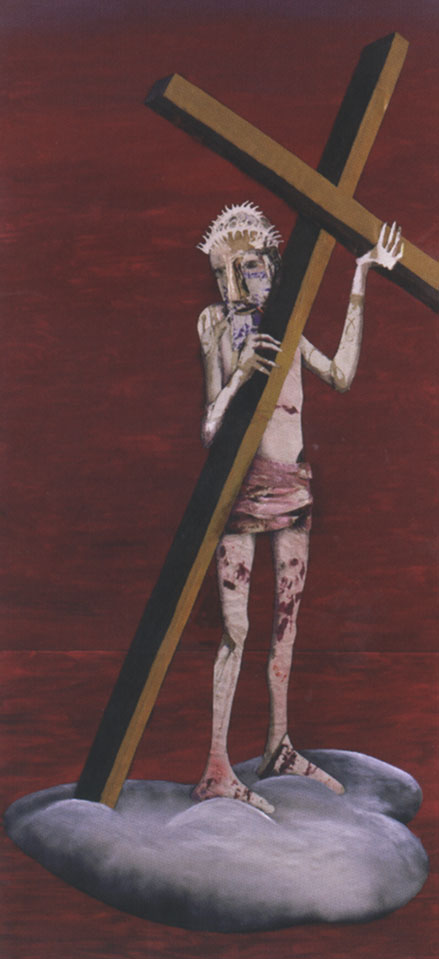

2. Jesus Christ, 2000, 107 1/2" x 50"

3. A Baptist Heaven, 2000, 98" x 72"

4. Humility, 2000, 55" x 42"

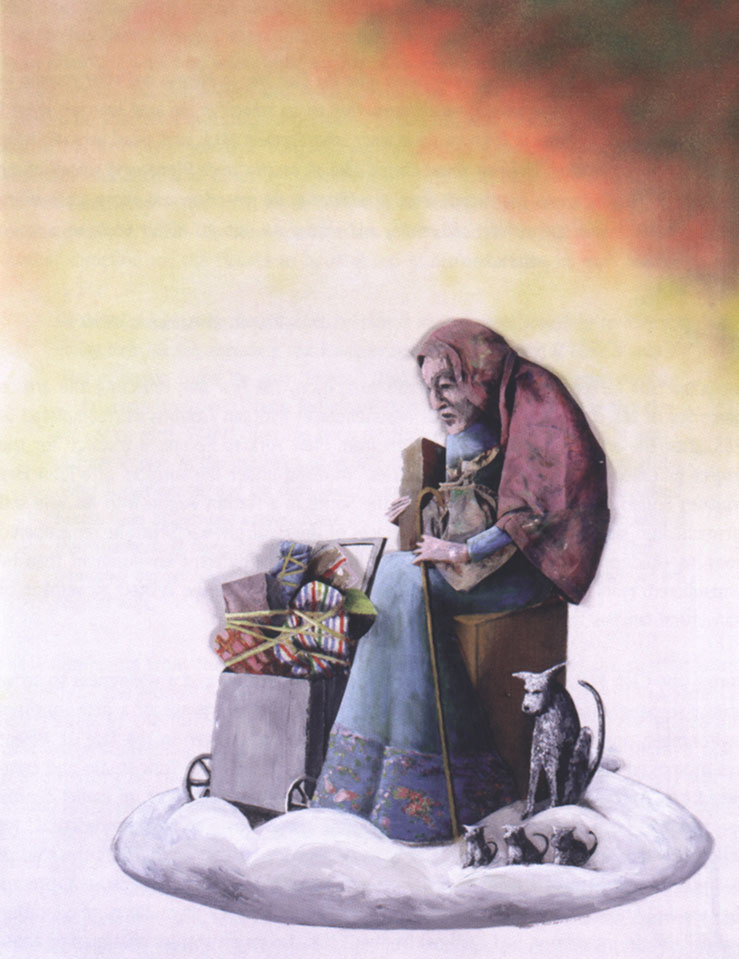

5. Homeless Going Home, 2000, 50" x 36"

6. Slave Study #2, 2000, 24" x 50"

Sculpture

7. Slave, 2000, 65.5" x 31" x 15"

8. Torah Bearer, 2000, 61" x 21" x 21"

Oil and Collage on Paper

9. Animal Lovers, 2000, 48 1/2" x 28 1/2"

10. Homage on High, 2000, 30" x 221/4"

11. Raising Cain, 2000, 30" x 22 1/2"

12. The Farmer Study I, 2000, 29 3/4" x 22

1/2"

13. Rabbi, 2000, 30" x 22 1/2"

14. Soul Singer, 2000, 22 1/4" x 14 3/4"

Oil on Canvas

15. The First Day, 1965, 36" x 35 1/2"

Carolina Arts is

published monthly by Shoestring Publishing Company, a subsidiary

of PSMG, Inc.

Copyright© 2003 by PSMG, Inc., which published Charleston

Arts from July 1987 - Dec. 1994 and South Carolina Arts

from Jan. 1995 - Dec. 1996. It also publishes Carolina Arts

Online, Copyright© 2003 by PSMG, Inc. All rights reserved

by PSMG, Inc. or by the authors of articles. Reproduction or use

without written permission is strictly prohibited. Carolina

Arts is available throughout North & South Carolina.